Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

When parathyroids work too hard

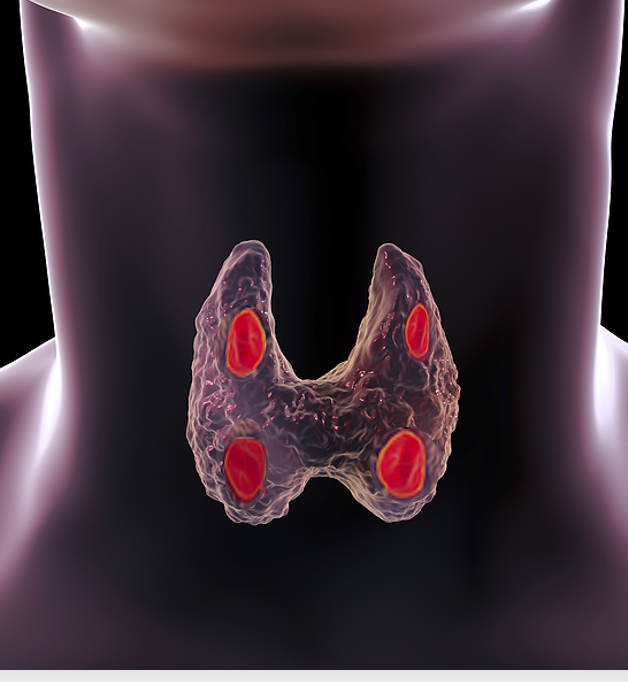

In secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT), the parathyroids are overactive, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels are high. Unlike primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT, though, the problem does not start with the parathyroids. Something else - usually low calcium levels - causes the parathyroid glands to release more PTH. The parathyroid glands exist to do one thing: maintain blood calcium levels. When the calcium is low, the parathyroids make more PTH to get the calcium up. If the blood calcium level stays low, the parathyroids just work harder and make more PTH. Over time, the PTH can get quite high and the glands can "bulk up" just like a muscle lifting heavy weights daily. Bulking up (called hyperplasia) allows the glands to produce more PTH.

PTH causes the bones to release calcium into the blood, to attempt to bring up blood calcium levels. The parathyroid glands care only about blood calcium levels, not bone calcium levels. So they will take out as much calcium from the bones as they can, if they need to get blood calcium levels up. Eventually, this will result in bone loss, which can progress to osteomalacia and fractures.

Causes of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

The most common cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism is chronic kidney disease, usually at the point where it requires dialysis. Severe chronic kidney disease leads to elevated levels of phosphorous and insufficient levels of active Vitamin D, both of which lead to low blood calcium levels. In renal hyperparathyroidism, the calcium levels often remain quite low, while PTH levels can rise dramatically, even above 1000 pg/ml (normal range is 20-65 pg/ml). This condition is usually treated medically, though if the PTH level remains above 500 pg/ml surgical intervention is usually necessary.

For patients who are not on dialysis, the most common cause of sHPT is calcium malabsorption in the intestines.

The following conditions lead to malabsorption of calcium:

We need to obtain calcium from our intestines. If the intestines cannot absorb calcium appropriately, calcium levels will drop and PTH levels will rise. Blood calcium levels may stay in the low-normal range as the bones release calcium. Eventually, the body's store of calcium will be so depleted that the blood calcium level will remain low and PTH will continue to rise.

Finally, an often-overlooked cause of secondary HPT is renal calcium leak. In this condition, the kidneys (which otherwise are working well) release too much calcium into the urine. This dumping of calcium leads to low blood calcium levels and high urine calcium levels. That high urine calcium can result in kidney stones. Doctors often confuse secondary HPT due to renal calcium leak with primary HPT. Kidney stones are "classic" symptoms of primary HPT, so a doctor will check a PTH level in someone with kidney stones, and notice that it is elevated. The doctor fails to note the low or low-normal calcium level, diagnoses primary HPT, and sends the patient to a surgeon. Unfortunately surgery is not going to help. The treatment for renal calcium leak is medical, most commonly a thiazide diuretic to stop the kidneys from releasing as much calcium.

Signs and Symptoms of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

Low calcium levels can make you feel tired, weak, and foggy, similar to chronically high calcium levels. Since elevated PTH levels are continuously removing calcium from the bones, you can also develop severe bone loss, with osteomalacia and fractures.

Treatment of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

First identify and address the underlying cause, if possible. Renal hyperparathyroidism is treated with active Vitamin D and dialysis, and managed by a nephrologist. For calcium malabsorption, the first-line treatment is aggressive supplementation with calcium and Vitamin D to get the calcium back into a normal range. This should be managed by someone experienced in handling secondary hyperparathyroidism, as it may take months to get Vitamin D, calcium levels, and PTH levels to stabilize. Renal calcium leak is treated with thiazide diuretics.

Bringing the calcium up to normal will allow the parathyroid glands to relax and stop making so much PTH. Surgical intervention is necessary in only some cases of secondary hyperparathyroidism, particularly if the glands have grown so much that they can no longer “turn off,” even when the calcium is back in normal range.

Primary vs. Secondary

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is characterized by a low blood calcium level. High calcium levels are associated with primary hyperparathyroidism, but not secondary. You cannot have secondary hyperparathyroidism if your calcium is high. For help in interpreting your calcium levels or diagnosing parathyroid disease, go to the Parathyroid Disease Analysis page.